Volume 20, Number 11—November 2014

Dispatch

Nosocomial Neonatal Legionellosis Associated with Water in Infant Formula, Taiwan

Abstract

We report 2 cases of neonatal Legionella infection associated with aspiration of contaminated water used in hospitals to make infant formula. The molecular profiles of Legionella strains isolated from samples from the infants and from water dispensers were indistinguishable. Our report highlights the need to consider nosocomial legionellosis among neonates who have respiratory symptoms.

Legionella infection was first reported in adults at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976 (1). The disease has a variety of clinical manifestations, ranging from mild respiratory tract illness to fatal pneumonia, especially among immunocompromised persons (2).

Legionella infection in neonates occurs rarely among both healthy and immunocompromised patients (3–8). Water birth and use of cold-mist humidification have been associated with neonatal legionellosis (9–11), but investigations of transmission modes are limited. We report 2 cases of neonatal Legionella infection associated with contaminated water used in infant formula in a hospital setting.

Case 1 involved a male neonate delivered by cesarean section in obstetric hospital A in Taiwan in April 2013, after an uneventful pregnancy of 38 weeks. He was fed infant formula in the hospital’s nursery. On postpartum day 7, he had a fever of 39°C and tachypnea and was taken to a tertiary hospital. Chest radiograph showed a ground-glass opacity in the middle lobe of his right lung, which subsequently developed into cavities. Microbiological testing of sputum and blood specimens yielded no definitive results. His pulmonary condition deteriorated during the following days. The case was reported to the Unknown Pathogen Discovery/Investigation Group at the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control for extensive etiologic survey. Multiplex real-time reverse transcription PCR showed sputum and blood specimens to be negative for adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, coronaviruses (229E, OC43, NL63, HKU1, and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus), metapneumovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza viruses 1–4, herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, human herpesviruses 6 and 7, bocavirus, parvovirus, enterovirus, and rhinovirus. However, Legionella pneumophila serogroup 5 was isolated from the sputum specimen. The patient was treated with antibacterial drugs and was discharged on postpartum day 17.

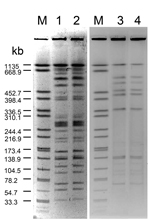

Water specimens from all sources with which the patient had contact were tested for Legionella by culture. L. pneumophila serogroup 4 was isolated from 3 tap water sources, and L. pneumophila serogroup 5 was isolated from the cold water source of the hot and cold water dispenser from which water for making infant formula was collected (Table). The water dispenser was located in the room next to the nursery. The hot water faucet provided boiled water at 95°100°C, and the cold water faucet provided unboiled water that was treated by a built-in reverse osmosis device. The pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles of the L. pneumophila serogroup 5 strains isolated from a sputum sample from the infant and those from a water sample from the water dispenser were indistinguishable (Figure). Both strains were sequence type 1032 (12).

Parents of the 175 neonates that were delivered ≤3 months before the patient’s birth in hospital A were interviewed by telephone; 3 of the 175 infants had fever within the first month of life. Serologic testing 3 weeks after their fever episodes was negative for IgM or IgG antibodies against L. pneumophila serogroups 1–6.

The water dispenser in hospital A was replaced with one that provided only hot water. The point-of-use filters were mounted on the water faucets in the nursery (Pall-AquaSafe Water Filter, Portsmouth, UK). All subsequent tests of water samples were negative for Legionella spp. No Legionella infection was identified in any neonate who was born after the patient’s birth in hospital A during the following 8 months.

Case 2 involved an asymptomatic male neonate delivered by cesarean section in obstetric hospital B in November 2013 after an uneventful pregnancy of 38 weeks. An optional screening test requested by the parents for severe combined immunodeficiency was negative. He remained asymptomatic and was fed infant formula throughout his 8-day stay in the hospital. At home on the day of discharge, he had a fever of 38.5°C and poor appetite. He had tachypnea and cyanosis of the lips during the following days, and on day 10 after birth, he was taken to the same tertiary hospital as case-patient 1. Bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and mild right pneumothorax were identified. The patient’s urine and sputum specimens tested positive for L. pneumophila serogroup 1. Azithromycin was administered on the day of admission. His clinical condition improved gradually. However, pulmonary fibrosis and pneumatoceles were identified later. He was discharged on day 55 after birth.

Testing of related environmental water specimens for Legionella spp. by culture was negative for all specimens except that from the cold water source of the hot and cold water dispenser in hospital B , which was positive for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (Table). The water dispenser in the nursery, which consisted of a tank containing boiled, hot water and another tank containing cool water pipelined from the boiled water tank, was used for making infant formula. The PFGE profiles of the strains from the patient and those from the water dispenser were indistinguishable (Figure). Both strains were sequence type 1.

The parents of the 79 neonates born ≤3 months before the patient’s birth in hospital B were interviewed by telephone. None of the neonates had fever during the first month of life. The water dispenser in hospital B was replaced with one that provided only hot water. All following water tests showed negative results. No Legionella infection was identified in any neonate who was born after the patient’s birth in hospital B during the following 3 months.

We report 2 cases of neonatal legionellosis associated with infant formula prepared with contaminated water. Only the cold water from both hospitals’ hot and cold water dispensers used for making infant formula was positive for L. pneumophila, with indistinguishable PFGE profiles and the same sequence types as those isolated from the neonates. Some environmental specimens were tested twice to compensate for inadequate sensitivity of the culture method and yielded the same results. No humidifier was used in either case. In the hospital where the first case-patient was identified, the water dispenser was not located in the nursery, which likely reduced the risk of transmitting Legionella spp. through contaminated aerosol droplets generated by the water dispenser.

Aspiration is a major transmission mode in hospital-acquired Legionella infection among adults (13,14). Neonatal Legionella infection through aspiration of contaminated water during water birth has been reported (9,10). Our results also indicate the Legionella infection described here was likely transmitted by aspiration of contaminated infant formula during the first days of life.

Both water dispensers were colonized with Legionella spp. Although the pervasiveness of these 2 problematic types of water dispenser is not known, hot and cold water dispensers are used in many hospitals in Taiwan. We speculate the complicated pipeline system and inappropriate maintenance of water dispensers might increase the risk for Legionella colonization, thus facilitating Legionella infection. Our report highlights the potential risk for Legionella transmission posed by contaminated water dispensers.

Few cases of neonatal legionellosis have been reported in the literature (3–5). Most cases were hospital acquired, and the patients had severe pneumonia that was associated with a high mortality rate (8,15). The manifestation of Legionella infection is not pathognomonic (15), therefore, underdiagnoses or delayed diagnoses combined with inappropriate treatment likely contribute substantially to mortality rates and severity of neonatal legionellosis. The 2 neonates described here survived after prompt diagnosis and treatment enabled by an extensive etiologic investigation and high suspicion of Legionella infection. Our report underscores the importance of suspecting and testing for Legionella infection when neonates have respiratory symptoms.

Dr. Wei is an infectious disease specialist and a medical officer in the Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan. His research interests include pediatric infectious diseases and field outbreak investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Central Regional Center of Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and the staff of the Health Bureau of Taichung City Government for their technical and logistic support in the conduct of this study.

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan (DOH102-DC-2502, DOH102-DC-2601, MOHW103-CDC-C-315-000103, MOHW103-CDC-C-315-000501 and MOHW103-CDC-C-315-000601).

References

- Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Orenstein W, Parkin WE, Beecham HJ, Sharrar RG, Legionnaires’ disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1189–97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sabria M, Yu VL. Hospital-acquired legionellosis: solutions for a preventable infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:368–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Greenberg D, Chiou CC, Famigilleti R, Lee TC, Yu VL. Problem pathogens: paediatric legionellosis—implications for improved diagnosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:529–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Levy I, Rubin LG. Legionella pneumonia in neonates: a literature review. J Perinatol. 1998;18:287–90 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Teare L, Millership S. Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 in a birthing pool. J Hosp Infect. 2012;82:58–60 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Famiglietti RF, Bakerman PR, Saubolle MA, Rudinsky M. Cavitary legionellosis in two immunocompetent infants. Pediatrics. 1997;99:899–903. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Holmberg RE Jr, Pavia AT, Montgomery D, Clark JM, Eggert LD. Nosocomial Legionella pneumonia in the neonate. Pediatrics. 1993;92:450–3 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Kassis I, Bamberger E, Nativ T, Sprecher H, Levy I, Fatal hospital-acquired Legionella pneumonia in a neonate. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:280–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Franzin L, Scolfaro C, Cabodi D, Valera M, Tovo PA. Legionella pneumophila pneumonia in a newborn after water birth: a new mode of transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:e103–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nagai T, Sobajima H, Iwasa M, Tsuzuki T, Kura F, Amemura-Maekawa J, Neonatal sudden death due to Legionella pneumonia associated with water birth in a domestic spa bath. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2227–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yiallouros PK, Papadouri T, Karaoli C, Papamichael E, Zeniou M, Pieridou-Bagatzouni D, First outbreak of nosocomial Legionella infection in term neonates caused by a cold mist ultrasonic humidifier. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:48–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Working Group for Legionella Infections [Internet]. Sequence-based typing database for Legionella pneumophila [cited 2014 May 23]. http://www.hpa-bioinformatics.org.uk/legionella/legionella_sbt/php/sbt_homepage.php.

- Blatt SP, Parkinson MD, Pace E, Hoffman P, Dolan D, Lauderdale P, Nosocomial Legionnaires’ disease: aspiration as a primary mode of disease acquisition. Am J Med. 1993;95:16–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Venezia RA, Agresta MD, Hanley EM, Urquhart K, Schoonmaker D. Nosocomial legionellosis associated with aspiration of nasogastric feedings diluted in tap water. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15:529–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yu VL, Lee TC. Neonatal legionellosis: the tip of the iceberg for pediatric hospital-acquired pneumonia? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:282–4 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This Article1These authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Table of Contents – Volume 20, Number 11—November 2014

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Chuen-Sheue Chiang, Centers for Disease Control, No. 161, Kun-Yang Street, Taipei, Taiwan

Top