Volume 22, Number 5—May 2016

Research

Projecting Month of Birth for At-Risk Infants after Zika Virus Disease Outbreaks

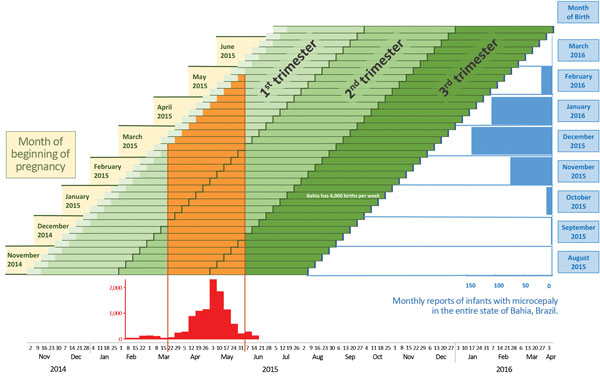

Figure 1

Figure 1. Projection of birth months after Zika virus transmission and occurrence of microcephaly, Salvador, Bahia State, Brazil. Weekly pregnancy cohorts are based on 40-week pregnancies and monthly reports of infants with microcephaly in Bahia State, Brazil, in relation to periods of high risk for Zika virus transmission. The epidemic curve shows cases treated for illness with rash in Salvadore, Brazil, estimated from (14). Complete monthly report data for January–March 2016 are not yet available.

References

- Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Epidemiological alert: neurologic syndrome, congenital malformations, and ZIKAV infection. Implications for public health in the Americas, 1 December 2015 [cited 2016 Feb 6]. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2015-dec-1-cha-epi-alert-zika-neuro-syndrome%2520%282%29.pdf

- Besnard M, Lastère S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V, Musso D. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20751. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, ZIKAV outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arzuza-Ortega L, Polo A, Pérez-Tatis G, López-García H, Parra E, Pardo-Herrera LC, Fatal sickle cell disease and Zika virus infection in girl from Colombia [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 May [cited 2016 Feb 23]. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, Horovitz DD, Cavalcanti DP, Pessoa A, Possible association between ZIKAV infection and microcephaly—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:59–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential association with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome [cited 2016 Jan 31]. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association-with-microcephaly-rapid-risk-assessment.pdf

- Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld P, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis A. ZIKAV intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:6–7 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ventura CV, Maia M, Bravo-Filho V, Gois AL, Belfort R Jr. ZIKAV in Brazil and macular atrophy in a child with microcephaly. Lancet. 2016;387:228. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. IHR procedures concerning public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC). 2016 [cited 2016 Feb 2]. http://www.who.int/ihr/procedures/pheic/en/

- Cha AE, Dennis B, Murphy B. Zika virus: WHO declares global public health emergency, says causal link to brain defects ‘strongly suspected.’ Washington Post. 2016 [cited 2016 Feb 2]. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/02/01/zika-virus-who-declares-global-public-health-emergency-given-rapid-spread-in-americas/

- Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Countries and territories with autochthonous transmission in the Americas reported in 2015–2016 [cited 2016 Feb 26]. http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11603&Itemid=41696&lang=en

- Hennessey M, Fischer M, Staples JE. ZIKAV spreads to new areas—region of the Americas, May 2015–January 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:55–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Live Birth Information System Brazil (SINASC). Characteristics of microcephaly and other defects. Panel 3 [cited 2016 Feb 6]. https://public.tableau.com/profile/bruno.zoca#!

- Cardoso CW, Paploski IA, Kikuti M, Rodrigues MS, Silva MM, Campos GS, Outbreak of exanthematous illness associated with Zika, chikungunya, and dengue viruses, Salvador, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2274–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Live Birth Information System Brazil (SINASC). Microcephaly in Brazil, 2000–2016. Panel 2 [cited 2016 Feb 26]. https://public.tableau.com/profile/bruno.zoca#!

- Live Birth Information System Brazil (SINASC). Live birth data for states in Brazil [cited 2016 Feb 4]. http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sinasc/cnv/nvBA.def

- Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Pollock TM. Consequences of confirmed maternal rubella at successive stages of pregnancy. Lancet. 1982;2:781–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bodéus M, Kabamba-Mukadi B, Zech F, Hubinont C, Bernard P, Goubau P. Human cytomegalovirus in utero transmission: follow-up of 524 maternal seroconversions. J Clin Virol. 2010;47:201–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pass RF, Fowler KB, Boppana SB, Britt WJ, Stagno S. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following first trimester maternal infection: symptoms at birth and outcome. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:216–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Victora CG, Schuler-Faccini L, Matijasevich A, Ribeiro E, Pessoa A, Barros FC. Microcephaly in Brazil: how to interpret reported numbers? Lancet. 2016;387:621–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ministry of Health Brazil. Monitoramento dos casos de microcefalia no Brasil [cited 2016 Feb 15]. http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2016/fevereiro/12/COES-Microcefalias-Informe-Epidemiologico-12-SE-05-2016-12fev2016-13h30.pdf

- Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, Mead PS, Meaney-Delman D, Renquist CM, Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:122–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Nelson JM, Fischer M, Staples JE, Karwowski MP, Mead P, Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection—United States, February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:182–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: April 13, 2016

Page updated: April 13, 2016

Page reviewed: April 13, 2016

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.