Volume 24, Number 10—October 2018

Research

Molecular Evolution, Diversity, and Adaptation of Influenza A(H7N9) Viruses in China

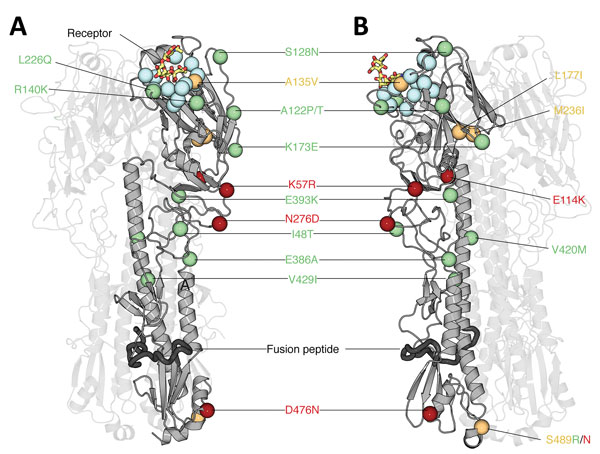

Figure 6

Figure 6. Structural analysis of amino acid changes in hemagglutinin in lineages B and C of influenza A(H7N9) viruses, China. Crystal structure of the homotrimeric H7 hemagglutinin bound to a human receptor analog (Protein Data Bank no. 4BSE) (27) (A) and rotated 90° counterclockwise (B) are shown. Two of the 3 protomers are displayed with high transparency to aid visualization. The carbon Cα positions of salient features are shown as spheres. Blue indicates receptor-binding residues, red indicates mutations in lineage B, green indicates mutations in lineage C, and orange indicates mutations in lineages B and C. Human receptor analog α2,6-SLN is shown as sticks colored according to constituent elements: carbon in orange, oxygen in red, and nitrogen in blue. Dark gray indicates the putative fusion peptide (32). Residues are numbered according to the H3 numbering system (Technical Appendix Table 2). A135 and L226 participate in receptor binding and thus are likely to modulate receptor specificity.

References

- Xiang N, Li X, Ren R, Wang D, Zhou S, Greene CM, et al. Assessing change in avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infections during the fourth epidemic—China, September 2015–August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1390–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cui L, Liu D, Shi W, Pan J, Qi X, Li X, et al. Dynamic reassortments and genetic heterogeneity of the human-infecting influenza A (H7N9) virus. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3142. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lam TT, Zhou B, Wang J, Chai Y, Shen Y, Chen X, et al. Dissemination, divergence and establishment of H7N9 influenza viruses in China. Nature. 2015;522:102–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu J, Lu J, Faria NR, Zeng X, Song Y, Zou L, et al. Effect of live poultry market interventions on influenza A(H7N9) virus, Guangdong, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:2104–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Iuliano AD, Jang Y, Jones J, Davis CT, Wentworth DE, Uyeki TM, et al. Increase in human infections with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus during the fifth epidemic—China, October 2016–February 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:254–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang X, Jiang H, Wu P, Uyeki TM, Feng L, Lai S, et al. Epidemiology of avian influenza A H7N9 virus in human beings across five epidemics in mainland China, 2013-17: an epidemiological study of laboratory-confirmed case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:822–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Artois J, Jiang H, Wang X, Qin Y, Pearcy M, Lai S, et al. Changing geographic patterns and risk factors for avian influenza A(H7N9) infections in humans, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:87–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang D, Yang L, Zhu W, Zhang Y, Zou S, Bo H, et al. Two outbreak sources of influenza A (H7N9) viruses have been established in China. J Virol. 2016;90:5561–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhu W, Zhou J, Li Z, Yang L, Li X, Huang W, et al. Biological characterisation of the emerged highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H7N9) viruses in humans, in mainland China, 2016 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017;22:30533. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ke C, Mok CKP, Zhu W, Zhou H, He J, Guan W, et al. Human infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1332–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang F, Bi Y, Wang J, Wong G, Shi W, Hu F, et al. Human infections with recently-emerging highly pathogenic H7N9 avian influenza virus in China. J Infect. 2017;75:71–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ke C, Lu J, Wu J, Guan D, Zou L, Song T, et al. Circulation of reassortant influenza A(H7N9) viruses in poultry and humans, Guangdong Province, China, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:2034–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lu J, Wu J, Zeng X, Guan D, Zou L, Yi L, et al. Continuing reassortment leads to the genetic diversity of influenza virus H7N9 in Guangdong, China. J Virol. 2014;88:8297–306. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Larsson A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3276–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lemey P, Rambaut A, Bedford T, Faria N, Bielejec F, Baele G, et al. Unifying viral genetics and human transportation data to predict the global transmission dynamics of human influenza H3N2. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003932. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lemey P, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Suchard MA. Bayesian phylogeography finds its roots. PLOS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000520. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Edwards CJ, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Welch JJ, Barnes I, Fulton TL, et al. Ancient hybridization and an Irish origin for the modern polar bear matriline. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1251–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–82.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yang Z. Among-site rate variation and its impact on phylogenetic analyses. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996;11:367–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xiong X, Martin SR, Haire LF, Wharton SA, Daniels RS, Bennett MS, et al. Receptor binding by an H7N9 influenza virus from humans. Nature. 2013;499:496–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schrödinger L. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. Version 1.8. New York: Schrödinger, LLC; 2015.

- Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Métoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:676–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD. Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1208–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murrell B, Wertheim JO, Moola S, Weighill T, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002764. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murrell B, Moola S, Mabona A, Weighill T, Sheward D, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. FUBAR: a fast, unconstrained bayesian approximation for inferring selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1196–205. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bhatt S, Holmes EC, Pybus OG. The genomic rate of molecular adaptation of the human influenza A virus. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2443–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Raghwani J, Bhatt S, Pybus OG. Faster adaptation in smaller populations: counterintuitive evolution of HIV during childhood infection. PLOS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004694. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapczynski DR, Pantin-Jackwood M, Guzman SG, Ricardez Y, Spackman E, Bertran K, et al. Characterization of the 2012 highly pathogenic avian influenza H7N3 virus isolated from poultry in an outbreak in Mexico: pathobiology and vaccine protection. J Virol. 2013;87:9086–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, Regnery H, Lim W, Hall H, et al. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science. 1998;279:393–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wiley DC, Wilson IA, Skehel JJ. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza haemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature. 1981;289:373–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Monne I, Fusaro A, Nelson MI, Bonfanti L, Mulatti P, Hughes J, et al. Emergence of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus from a low-pathogenic progenitor. J Virol. 2014;88:4375–88. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Wit E, Munster VJ, van Riel D, Beyer WE, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, et al. Molecular determinants of adaptation of highly pathogenic avian influenza H7N7 viruses to efficient replication in the human host. J Virol. 2010;84:1597–606. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schmeisser F, Vasudevan A, Verma S, Wang W, Alvarado E, Weiss C, et al. Antibodies to antigenic site A of influenza H7 hemagglutinin provide protection against H7N9 challenge. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117108. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature. 2013;501:556–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cattoli G, Milani A, Temperton N, Zecchin B, Buratin A, Molesti E, et al. Antigenic drift in H5N1 avian influenza virus in poultry is driven by mutations in major antigenic sites of the hemagglutinin molecule analogous to those for human influenza virus. J Virol. 2011;85:8718–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xu L, Bao L, Deng W, Dong L, Zhu H, Chen T, et al. Novel avian-origin human influenza A(H7N9) can be transmitted between ferrets via respiratory droplets. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:551–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yang L, Zhu W, Li X, Chen M, Wu J, Yu P, et al. Genesis and spread of newly emerged highly pathogenic H7N9 avian viruses in mainland China. J Virol. 2017;91:e01277–17.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- García M, Crawford JM, Latimer JW, Rivera-Cruz E, Perdue ML. Heterogeneity in the haemagglutinin gene and emergence of the highly pathogenic phenotype among recent H5N2 avian influenza viruses from Mexico. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1493–504. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Horimoto T, Rivera E, Pearson J, Senne D, Krauss S, Kawaoka Y, et al. Origin and molecular changes associated with emergence of a highly pathogenic H5N2 influenza virus in Mexico. Virology. 1995;213:223–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Suarez DL, Senne DA, Banks J, Brown IH, Essen SC, Lee CW, et al. Recombination resulting in virulence shift in avian influenza outbreak, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:693–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapczynski DR, Pantin-Jackwood M, Guzman SG, Ricardez Y, Spackman E, Bertran K, et al. Characterization of the 2012 highly pathogenic avian influenza H7N3 virus isolated from poultry in an outbreak in Mexico: pathobiology and vaccine protection. J Virol. 2013;87:9086–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pasick J, Handel K, Robinson J, Copps J, Ridd D, Hills K, et al. Intersegmental recombination between the haemagglutinin and matrix genes was responsible for the emergence of a highly pathogenic H7N3 avian influenza virus in British Columbia. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:727–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shi J, Deng G, Kong H, Gu C, Ma S, Yin X, et al. H7N9 virulent mutants detected in chickens in China pose an increased threat to humans. Cell Res. 2017;27:1409–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Imai M, Watanabe T, Kiso M, Nakajima N, Yamayoshi S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, et al. A highly pathogenic avian H7N9 influenza virus isolated from a human is lethal in some ferrets infected via respiratory droplets. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:615–626.e8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

2These senior authors jointly supervised this study.