Volume 24, Number 2—February 2018

Research

Yersinia pestis Survival and Replication in Potential Ameba Reservoir

Figure 1

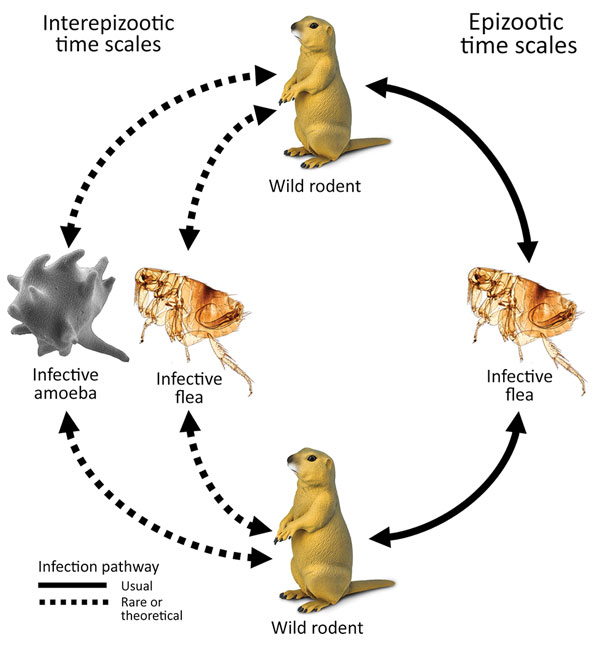

Figure 1. Infection pathways for plague. During plague epizootics, transmission occurs through flea vectors within meta-populations of ground-dwelling rodents. It is unknown by what route or mechanism Yersinia pestis is maintained during interepizootic periods of plague quiescence. Previous research on fleas has not strongly supported their reservoir potential across interepizootic periods (3). The experiment and analysis of this study test the hypothesis that amoeboid species demonstrate reservoir potential for Y. pestis. If Y. pestis is maintained within ameba reservoirs, we suspect that epizootic recrudescence may occur when infected soilborne amebae enter the bloodstream of naive rodent hosts (by entering wounds from antagonistic host-to-host interactions or burrowing activities). Amebae typically lyse when incubated at 37°C and simultaneously release their intracellular cargo, potentially initiating an infection.

References

- Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis—etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:35–66.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bertherat E; World Health Organization. Plague around the world, 2010–2015. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016;91:89–93.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Webb CT, Brooks CP, Gage KL, Antolin MF. Classic flea-borne transmission does not drive plague epizootics in prairie dogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6236–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Girard JM, Wagner DM, Vogler AJ, Keys C, Allender CJ, Drickamer LC, et al. Differential plague-transmission dynamics determine Yersinia pestis population genetic structure on local, regional, and global scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8408–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Snäll T, O’Hara RB, Ray C, Collinge SK. Climate-driven spatial dynamics of plague among prairie dog colonies. Am Nat. 2008;171:238–48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eisen RJ, Gage KL. Adaptive strategies of Yersinia pestis to persist during inter-epizootic and epizootic periods. Vet Res. 2009;40:01.

- Gibbons HS, Krepps MD, Ouellette G, Karavis M, Onischuk L, Leonard P, et al. Comparative genomics of 2009 seasonal plague (Yersinia pestis) in New Mexico. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31604. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lowell JL, Antolin MF, Andersen GL, Hu P, Stokowski RP, Gage KL. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms reveal spatial diversity among clones of Yersinia pestis during plague outbreaks in Colorado and the western United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015;15:291–302. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salkeld DJ, Stapp P, Tripp DW, Gage KL, Lowell J, Webb CT, et al. Ecological traits driving the outbreaks and emergence of zoonotic pathogens. Bioscience. 2016;66:118–29. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Pavlovsky EN. Natural nidality of transmissible diseases, with special reference to the landscape epidemiology of zooanthroponoses. Urbana (IL): University of Illinois Press; 1966.

- Gage KL, Kosoy MY. Natural history of plague: perspectives from more than a century of research. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:505–28. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ayyadurai S, Houhamdi L, Lepidi H, Nappez C, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Long-term persistence of virulent Yersinia pestis in soil. Microbiology. 2008;154:2865–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Benavides-Montaño JA, Vadyvaloo V. Yersinia pestis resists predation by Acanthamoeba castellanii and exhibits prolonged intracellular survival. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e00593–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Greub G, Raoult D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:413–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hilbi H, Weber SS, Ragaz C, Nyfeler Y, Urwyler S. Environmental predators as models for bacterial pathogenesis. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:563–75. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bichai F, Payment P, Barbeau B. Protection of waterborne pathogens by higher organisms in drinking water: a review. Can J Microbiol. 2008;54:509–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salah IB, Ghigo E, Drancourt M. Free-living amoebae, a training field for macrophage resistance of mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:894–905. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Thomas V, McDonnell G, Denyer SP, Maillard J-Y. Free-living amoebae and their intracellular pathogenic microorganisms: risks for water quality. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:231–59. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wheat WH, Casali AL, Thomas V, Spencer JS, Lahiri R, Williams DL, et al. Long-term survival and virulence of Mycobacterium leprae in amoebal cysts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3405. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pujol C, Bliska JB. The ability to replicate in macrophages is conserved between Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5892–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lambrecht E, Baré J, Chavatte N, Bert W, Sabbe K, Houf K. Protozoan cysts act as a survival niche and protective shelter for foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:5604–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Santos-Montañez J, Benavides-Montaño JA, Hinz AK, Vadyvaloo V. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 survives and replicates in trophozoites and persists in cysts of Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015;362:fnv091. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Savage LT, Reich RM, Hartley LM, Stapp P, Antolin MF. Climate, soils, and connectivity predict plague epizootics in black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus). Ecol Appl. 2011;21:2933–43. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Collinge SK, Johnson WC, Ray C, Matchett R, Grensten J, Cully JF Jr, et al. Landscape structure and plague occurrence in black-tailed prairie dogs on grasslands of the western USA. Landsc Ecol. 2005;20:941–55. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Easterday WR, Kausrud KL, Star B, Heier L, Haley BJ, Ageyev V, et al. An additional step in the transmission of Yersinia pestis? ISME J. 2012;6:231–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ke Y, Chen Z, Yang R. Yersinia pestis: mechanisms of entry into and resistance to the host cell. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:106 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Connor MG, Pulsifer AR, Price CT, Abu Kwaik Y, Lawrenz MB. Yersinia pestis requires host Rab1b for survival in macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005241. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nikul’shin SV, Onatskaia TG, Lukanina LM, Bondarenko AI. [Associations of the soil amoeba Hartmannella rhysodes with the bacterial causative agents of plague and pseudotuberculosis in an experiment] [in Russian]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1992; (

9-10 ):2–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar - Pushkareva VI. [Experimental evaluation of interaction between Yersinia pestis and soil infusoria and possibility of prolonged preservation of bacteria in the protozoan oocysts] [in Russian]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2003; (

4 ):40–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar - Barker J, Brown MR. Trojan horses of the microbial world: protozoa and the survival of bacterial pathogens in the environment. Microbiology. 1994;140:1253–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Link VB. A history of plague in United States of America. Public Health Monogr. 1955;26:1–120.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lagkouvardos I, Shen J, Horn M. Improved axenization method reveals complexity of symbiotic associations between bacteria and acanthamoebae. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2014;6:383–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Charette SJ, Cosson P. Preparation of genomic DNA from Dictyostelium discoideum for PCR analysis. Biotechniques. 2004;36:574–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Le Calvez T, Trouilhé M-C, Humeau P, Moletta-Denat M, Frère J, Héchard Y. Detection of free-living amoebae by using multiplex quantitative PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 2012;26:116–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schuster FL. Cultivation of pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amebas. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:342–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Thomas V, Herrera-Rimann K, Blanc DS, Greub G. Biodiversity of amoebae and amoeba-resisting bacteria in a hospital water network. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2428–38. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fey P, Dodson R, Basu S, Chisholm R. One stop shop for everything Dictyostelium: dictyBase and the dicty stock center in 2012. In: Eichinger L, Rivero F, editors. Dictyostelium discoideum protocols. Methods in molecular biology (methods and protocols), vol 983. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013. p. 59–92.

- Molmeret M, Horn M, Wagner M, Santic M, Abu Kwaik Y. Amoebae as training grounds for intracellular bacterial pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:20–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Straley SC, Perry RD. Environmental modulation of gene expression and pathogenesis in Yersinia. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:310–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grabenstein JP, Fukuto HS, Palmer LE, Bliska JB. Characterization of phagosome trafficking and identification of PhoP-regulated genes important for survival of Yersinia pestis in macrophages. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3727–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pujol C, Klein KA, Romanov GA, Palmer LE, Cirota C, Zhao Z, et al. Yersinia pestis can reside in autophagosomes and avoid xenophagy in murine macrophages by preventing vacuole acidification. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2251–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clarke M, Lohan AJ, Liu B, Lagkouvardos I, Roy S, Zafar N, et al. Genome of Acanthamoeba castellanii highlights extensive lateral gene transfer and early evolution of tyrosine kinase signaling. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eichinger L, Pachebat JA, Glöckner G, Rajandream M-A, Sucgang R, Berriman M, et al. The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2005;435:43–57. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Buzoleva LS, Sidorenko ML. [Influence of gaseous metabolites of soil bacteria on the multiplication of Listeria monocytogenes and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis.] [in Russian]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2005; (

2 ):7–11.PubMedGoogle Scholar - Somova LM, Buzoleva LS, Isachenko AS, Somov GP. [Adaptive ultrastructural changes in soil-resident Yersinia pseudotuberculosis bacteria] [in Russian]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2006; (

3 ):36–40.PubMedGoogle Scholar - Pawlowski DR, Metzger DJ, Raslawsky A, Howlett A, Siebert G, Karalus RJ, et al. Entry of Yersinia pestis into the viable but nonculturable state in a low-temperature tap water microcosm. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17585. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar