Volume 24, Number 9—September 2018

Research Letter

Case of Microcephaly after Congenital Infection with Asian Lineage Zika Virus, Thailand

Figure

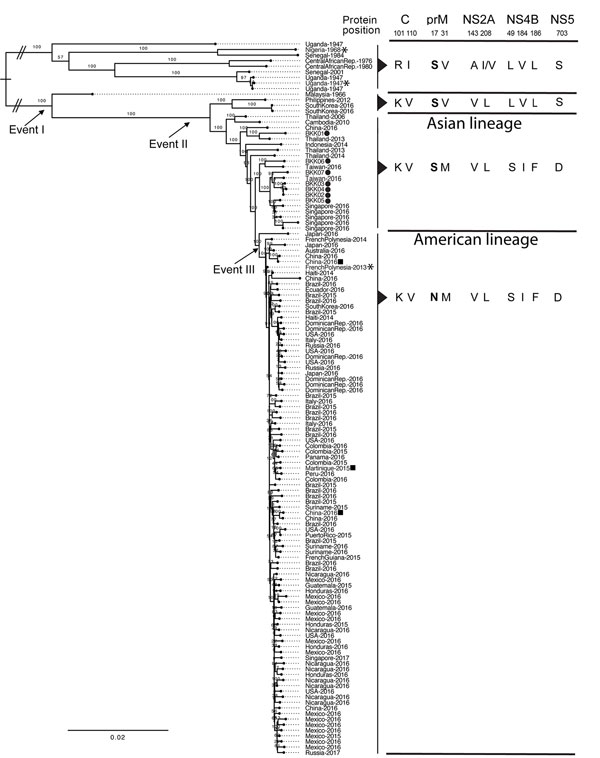

Figure. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of nonredundant Zika virus genomes including 7 isolates from patients in Thailand, 2016–2017, and amino acid changes corresponding with 3 evolutionary events (2). Circles indicate the Zika virus isolates from this report; the Zika virus strains used by Liang et al. (3) are indicated by asterisks and Yuan et al. (4) by squares. The key amino acid residue changes corresponding with the 3 evolutionary events (2) are shown, and the conserved amino acid substitution S17N, present in the American lineage but not in the other lineages, is in bold. The amino acid residues of the 7 isolates from this report are identical to those of the other Asian lineage isolates. C, capsid; prM, premembrane; NS, nonstructural protein. Scale bar indicates nucleotide changes per basepair.

References

- Lim SK, Lim JK, Yoon IK. An update on Zika virus in Asia. Infect Chemother. 2017;49:91–100. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jun SR, Wassenaar TM, Wanchai V, Patumcharoenpol P, Nookaew I, Ussery DW. Suggested mechanisms for Zika virus causing microcephaly: what do the genomes tell us? BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18(Suppl 14):471. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liang Q, Luo Z, Zeng J, Chen W, Foo SS, Lee SA, et al. Zika virus NS4A and NS4B proteins deregulate akt-mTOR signaling in human fetal neural stem cells to inhibit neurogenesis and induce autophagy. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:663–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yuan L, Huang XY, Liu ZY, Zhang F, Zhu XL, Yu JY, et al. A single mutation in the prM protein of Zika virus contributes to fetal microcephaly. Science. 2017;358:933–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Driggers RW, Ho CY, Korhonen EM, Kuivanen S, Jääskeläinen AJ, Smura T, et al. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2142–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sohan K, Cyrus CA. Ultrasonographic observations of the fetal brain in the first 100 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;139:278–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Parra-Saavedra M, Reefhuis J, Piraquive JP, Gilboa SM, Badell ML, Moore CA, et al. Serial head and brain imaging of 17 fetuses with confirmed Zika virus infection in Colombia, South America. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:207–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kleber de Oliveira W, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WT, do Carmo GM, Henriques CM, Coelho GE, et al. Increase in reported prevalence of microcephaly in infants born to women living in areas with confirmed Zika virus transmission during the first trimester of pregnancy—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:242–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cuevas EL, Tong VT, Rozo N, Valencia D, Pacheco O, Gilboa SM, et al. Preliminary report of microcephaly potentially associated with Zika virus infection during pregnancy—Colombia, January–November 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1409–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, Lee EH, Rice ME, Bingham A, et al.; U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry Collaboration. Vital Signs: Update on Zika virus–associated birth defects and evaluation of all U.S. infants with congenital Zika virus exposure—U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:366–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These first authors contributed equally to this article.

2These senior authors contributed equally to this article.