Volume 25, Number 12—December 2019

Dispatch

Divergent Barmah Forest Virus from Papua New Guinea

Figure 2

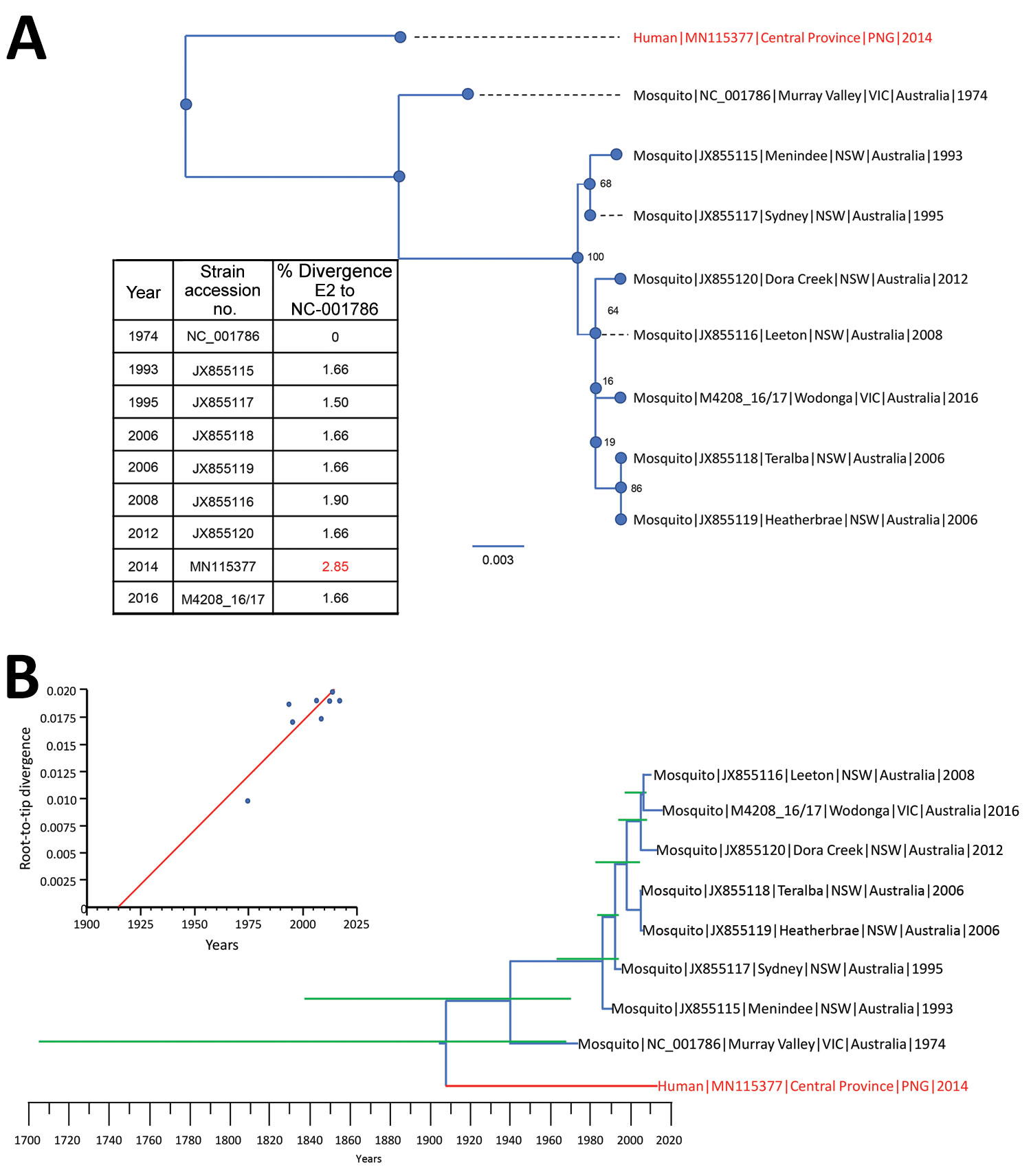

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships between 9 full-length (1,263 nt) Barmah Forest virus (BFV) envelope (E) protein genes. A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree constructed from 8 full-length Australia BFV E2 sequences (blue) and a BFV E2 sequences from an isolate from a child in Papua New Guinea (red) by using the best-fit nucleotide substitution model in IQ-Tree version 1.5 (11). Bootstrap values were estimated by using 1,000 replicates; percentages are indicated on branch nodes. Inset table shows E2 nucleotide divergence compared with that for prototype strain BH2193 (RefSeq accession no. NC_001786.1). Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. B) Molecular clock analysis using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo method in BEAST (12) for 9 complete BFV E2 sequences (blue) spanning 1974–2016. Red indicates BFV from an isolate from a child in Papua New Guinea. Green lines indicate 95% CIs. Inset shows temporal analysis of root-to-tip linear regression by using TempEst version 1.5 (13). Slope, 1.98 × 10−4; X-intercept, 1914.2; correlation coefficient, 0.86; R2, 0.743; residual mean squared, 2.76 × 10−6. NSW, New South Wales; VIC, Victoria.

References

- Mackenzie JS, Lindsay MD, Coelen RJ, Broom AK, Hall RA, Smith DW. Arboviruses causing human disease in the Australasian zoogeographic region. Arch Virol. 1994;136:447–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marshall ID, Woodroofe GM, Hirsch S. Viruses recovered from mosquitoes and wildlife serum collected in the Murray Valley of South-eastern Australia, February 1974, during an epidemic of encephalitis. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1982;60:457–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Doggett SL, Russell RC, Clancy J, Haniotis J, Cloonan MJ. Barmah Forest virus epidemic on the south coast of New South Wales, Australia, 1994-1995: viruses, vectors, human cases, and environmental factors. J Med Entomol. 1999;36:861–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ryan PA, Kay BH. Vector competence of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Maroochy Shire, Australia, for Barmah Forest virus. J Med Entomol. 1999;36:856–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jeffery JA, Ryan PA, Lyons SA, Kay BH. Vector competence of Coquillettidia linealis (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) for Ross River and Barmah Forest viruses. Aust J Entomol. 2002;41:339–44. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Quinn HE, Gatton ML, Hall G, Young M, Ryan PA. Analysis of Barmah Forest virus disease activity in Queensland, Australia, 1993-2003: identification of a large, isolated outbreak of disease. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:882–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ehlkes L, Eastwood K, Webb C, Durrheim D. Surveillance should be strengthened to improve epidemiological understandings of mosquito-borne Barmah Forest virus infection. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2012;3:63–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Knope K, Doggett SL, Jansen CC, Johansen CA, Kurucz N, Feldman R, et al. Arboviral diseases and malaria in Australia, 2014–15. Annual report of the National Arbovirus and Malaria Advisory Committee. Communicable Diseases Intelligence (2018). 2019;Apr 15:43.

- Flexman JP, Smith DW, Mackenzie JS, Fraser JR, Bass SP, Hueston L, et al. A comparison of the diseases caused by Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus. Med J Aust. 1998;169:159–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lee E, Stocks C, Lobigs P, Hislop A, Straub J, Marshall I, et al. Nucleotide sequence of the Barmah Forest virus genome. Virology. 1997;227:509–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:268–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rambaut A, Lam TT, Max Carvalho L, Pybus OG. Exploring the temporal structure of heterochronous sequences using TempEst (formerly Path-O-Gen). Virus Evol. 2016;2:

vew007 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Sanjuán R, Domingo-Calap P. Mechanisms of viral mutation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:4433–48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar