Volume 29, Number 11—November 2023

Research

Human Salmonellosis Outbreak Linked to Salmonella Typhimurium Epidemic in Wild Songbirds, United States, 2020–2021

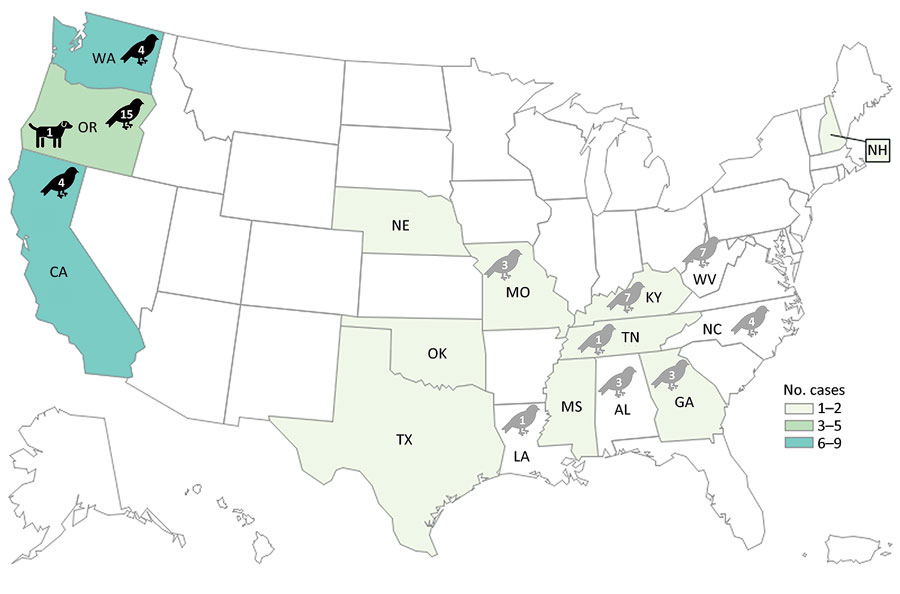

Figure 1

Figure 1. Geographic locations of human Salmonella Typhimurium cases in the United States, 2020–2021. Colored shading indicates number of cases by state; black bird icons indicate states that detected the outbreak strain of Salmonella Typhimurium from wild birds (within 0–12 allele differences based on core genome multilocus sequence typing). One isolate was obtained from a dog’s mouth wound at a veterinary hospital in Oregon (dog icon) and matched the outbreak strain. Numbers of genetically related isolates obtained from wild birds are indicated within animal icons. Salmonella Typhimurium was also detected in wild birds as part of the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study at the University of Georgia (gray bird icons); those isolates were serotyped at the National Veterinary Services Laboratory (30), but whole-genome sequencing was not performed to confirm relatedness to the outbreak strain.

References

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:7–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beshearse E, Bruce BB, Nane GF, Cooke RM, Aspinall W, Hald T, et al. Attribution of illnesses transmitted by food and water to comprehensive transmission pathways using structured expert judgment, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:182–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hale CR, Scallan E, Cronquist AB, Dunn J, Smith K, Robinson T, et al. Estimates of enteric illness attributable to contact with animals and their environments in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 5):S472–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shane AL, Mody RK, Crump JA, Tarr PI, Steiner TS, Kotloff K, et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:e45–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hall AJ, Saito EK. Avian wildlife mortality events due to salmonellosis in the United States, 1985-2004. J Wildl Dis. 2008;44:585–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hernandez SM, Keel K, Sanchez S, Trees E, Gerner-Smidt P, Adams JK, et al. Epidemiology of a Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain associated with a songbird outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7290–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tizard I. Salmonellosis in wild birds. Seminars in avian and Exotic Pet Medicine. 2004;13:50–66.

- Alley MR, Connolly JH, Fenwick SG, Mackereth GF, Leyland MJ, Rogers LE, et al. An epidemic of salmonellosis caused by Salmonella Typhimurium DT160 in wild birds and humans in New Zealand. N Z Vet J. 2002;50:170–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Daoust P, Prescott JF. Salmonellosis. In: Thomas N, Hunter DB, Atkinson CT, editors. Infectious disease of wild birds. Ames (IA); Blackwell Publishing, 2007. p. 270–288.

- Hudson CR, Quist C, Lee MD, Keyes K, Dodson SV, Morales C, et al. Genetic relatedness of Salmonella isolates from nondomestic birds in Southeastern United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1860–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lawson B, de Pinna E, Horton RA, Macgregor SK, John SK, Chantrey J, et al. Epidemiological evidence that garden birds are a source of human salmonellosis in England and Wales. PLoS One. 2014;9:

e88968 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Mather AE, Lawson B, de Pinna E, Wigley P, Parkhill J, Thomson NR, et al. Genomic analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from wild passerines in England and Wales. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:6728–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Refsum T, Vikøren T, Handeland K, Kapperud G, Holstad G. Epidemiologic and pathologic aspects of Salmonella typhimurium infection in passerine birds in Norway. J Wildl Dis. 2003;39:64–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Smith OM, Snyder WE, Owen JP. Are we overestimating risk of enteric pathogen spillover from wild birds to humans? Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2020;95:652–79. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamer SA, Lehrer E, Magle SB. Wild birds as sentinels for multiple zoonotic pathogens along an urban to rural gradient in greater Chicago, Illinois. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;59:355–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murray MH, Becker DJ, Hall RJ, Hernandez SM. Wildlife health and supplemental feeding: A review and management recommendations. Biol Conserv. 2016;204:163–74. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Robb GN, McDonald RA, Chamberlain DE, Bearhop S. Food for thought: supplementary feeding as a driver of ecological change in avian populations. Front Ecol Environ. 2008;6:476–84. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Fuller RA, Irvine KN. Interactions between people and nature in urban environments. In: Gaston KJ, editor. Urban ecology (Ecological Reviews). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. p. 134-171.

- Jones DN, James Reynolds S. Feeding birds in our towns and cities: a global research opportunity. J Avian Biol. 2008;39:265–71. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Marzluff JM. Worldwide urbanization and its effects on birds. In: Marzluff JM, Bowman R, Donnelly R, editors. Avian ecology and conversation in an urbanizing world. Boston: Springer; 2011. p. 19–47.

- Fuller T, Bensch S, Müller I, Novembre J, Pérez-Tris J, Ricklefs RE, et al. The ecology of emerging infectious diseases in migratory birds: an assessment of the role of climate change and priorities for future research. EcoHealth. 2012;9:80–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mills JN, Gage KL, Khan AS. Potential influence of climate change on vector-borne and zoonotic diseases: a review and proposed research plan. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1507–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapperud G, Stenwig H, Lassen J. Epidemiology of Salmonella typhimurium O:4-12 infection in Norway: evidence of transmission from an avian wildlife reservoir. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:774–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tauni MA, Osterlund A. Outbreak of Salmonella typhimurium in cats and humans associated with infection in wild birds. J Small Anim Pract. 2000;41:339–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sykes JE, Marks SL. Salmonellosis. In: Sykes JE, editor. Canine and feline infectious diseases. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier Inc.; 2014. p. 437–44.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information Pathogen Detection Project. [cited 2021 Dec 8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/

- Katz LS, Griswold T, Williams-Newkirk AJ, Wagner D, Petkau A, Sieffert C, et al. A comparative analysis of the lyve-set phylogenomics pipeline for genomic epidemiology of foodborne pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:375. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PulseNet methods and protocols: Whole genome sequencing (WGS). 2016 [cited 2021 Dec 6] https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/wgs.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet). 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 8] https://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/index.html.

- Morningstar-Shaw BR, Mackie TA, Barker DK, Palmer EA. Salmonella serotypes isolated from animals and related sources. 2016 [cited 2022 Nov 2] https://www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/salmonella-serotypes-isolated-animals-and-related-sources-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella outbreak linked to wild songbirds. 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 8]. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/typhimurium-04-21/index.html

- Newton I. Irruptive migration. In: Breed MD, Moore J, editors. Encyclopedia of animal behavior, 1st edition. Academic Press. Oxford: American Press; 2010. p. 221–229.

- Lawson B, Robinson RA, Toms MP, Risely K, MacDonald S, Cunningham AA. Health hazards to wild birds and risk factors associated with anthropogenic food provisioning. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373:

20170091 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Wilcoxen TE, Horn DJ, Hogan BM, Hubble CN, Huber SJ, Flamm J, et al. Effects of bird-feeding activities on the health of wild birds. Conserv Physiol. 2015;3:

cov058 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Cherry B, Burns A, Johnson GS, Pfeiffer H, Dumas N, Barrett D, et al. Salmonella Typhimurium outbreak associated with veterinary clinic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:2249–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Loyd KAT, Hernandez SM, Carroll JP, Abernathy KJ, Marshall GJ. Quantifying free-roaming domestic cat predation using animal-borne video cameras. Biol Conserv. 2013;160:183–9. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Feliciano LM, Underwood TJ, Aruscavage DF. The effectiveness of bird feeder cleaning methods with and without debris. Wilson J Ornithol. 2018;130:313–20. DOIGoogle Scholar

1These authors contributed equally to this article.