Volume 29, Number 11—November 2023

Synopsis

Detection of Novel US Neisseria meningitidis Urethritis Clade Subtypes in Japan

Figure 2

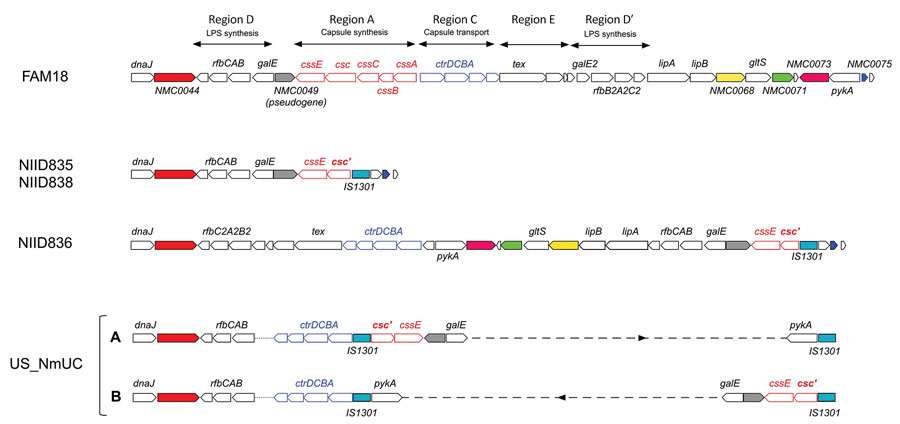

Figure 2. Organization of genes within the cps locus of Neisseria meningitidis isolates in study of detection of novel US N. meningitidis urethritis clade subtypes in Japan. N. meningitidis isolates from Japan (NIID835, NIID836, NIID838) and United States (US_NmUC) were compared with N. meningitidis strain FAM18 (GenBank accession no. AM421808). Open red arrows indicate the cssA, cssB, cssC, csc, and cssE genes in region A responsible for capsule synthesis and open blue arrows the ctrD, ctrC, ctrB, and ctrA genes (in that order) in region C responsible for capsule transport. Insertion sequence IS1301 is indicated. Open reading frames identical to NMC0044 (solid red), NMC0049 (gray), NMC0068 (yellow), NMC0071 (green), NMC0073 (pink), and NMC0075 (blue) in FAM18 are shown for each isolate. Partial deletion is indicated for the csc gene (csc′). The cps locus for US_NmUC had 2 configurations created by a ≈20-kb genome inversion between 2 IS1301 sequences (designated as A and B). Gene alignments in the region between the 2 IS1301 sequences have been omitted and are indicated by the dashed line. Although ctrD, ctrC, ctrB, and ctrA genes were shown to be proximal to dnaJ (12), contigs containing the dnaJ-rfbC, rfbA, and rfbB genes and the ctrD, ctrC, ctrB, and ctrA genes (shown on the left side of A and B), as well as 2 IS1301 and pykA genes (shown on the right side of A and B), were not connected by our analysis because of the absence of US_NmUC long-read sequences. Therefore, unidentified connections of the 2 contigs are indicated by a dotted line.

References

- Acevedo R, Bai X, Borrow R, Caugant DA, Carlos J, Ceyhan M, et al. The Global Meningococcal Initiative meeting on prevention of meningococcal disease worldwide: Epidemiology, surveillance, hypervirulent strains, antibiotic resistance and high-risk populations. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18:15–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taha MK, Martinon-Torres F, Köllges R, Bonanni P, Safadi MAP, Booy R, et al. Equity in vaccination policies to overcome social deprivation as a risk factor for invasive meningococcal disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21:659–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mustapha MM, Marsh JW, Harrison LH. Global epidemiology of capsular group W meningococcal disease (1970-2015): Multifocal emergence and persistence of hypervirulent sequence type (ST)-11 clonal complex. Vaccine. 2016;34:1515–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schmink S, Watson JT, Coulson GB, Jones RC, Diaz PS, Mayer LW, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis isolates from an outbreak of meningococcal disease among men who have sex with men, Chicago, Illinois, 2003. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3768–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marcus U, Vogel U, Schubert A, Claus H, Baetzing-Feigenbaum J, Hellenbrand W, et al. A cluster of invasive meningococcal disease in young men who have sex with men in Berlin, October 2012 to May 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20523. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kratz MM, Weiss D, Ridpath A, Zucker JR, Geevarughese A, Rakeman J, et al. Community-based outbreak of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C infection in men who have sex with men, New York City, New York, USA, 2010–2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1379–86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taha MK, Claus H, Lappann M, Veyrier FJ, Otto A, Becher D, et al. Evolutionary events associated with an outbreak of meningococcal disease in men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2016;11:

e0154047 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Nanduri S, Foo C, Ngo V, Jarashow C, Civen R, Schwartz B, et al. Outbreak of serogroup C meningococcal disease primarily affecting men who have sex with men—Southern California, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:939–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Folaranmi TA, Kretz CB, Kamiya H, MacNeil JR, Whaley MJ, Blain A, et al. Increased risk for meningococcal disease among men who have sex with men in the United States, 2012–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:756–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bazan JA, Peterson AS, Kirkcaldy RD, Briere EC, Maierhofer C, Turner AN, et al. Notes from the field: increase in Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis among men at two sentinel clinics—Columbus, Ohio, and Oakland County, Michigan, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:550–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Toh E, Gangaiah D, Batteiger BE, Williams JA, Arno JN, Tai A, et al. Neisseria meningitidis ST11 complex isolates associated with nongonococcal urethritis, Indiana, USA, 2015–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:336–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tzeng YL, Bazan JA, Turner AN, Wang X, Retchless AC, Read TD, et al. Emergence of a new Neisseria meningitidis clonal complex 11 lineage 11.2 clade as an effective urogenital pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:4237–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bazan JA, Stephens DS, Turner AN. Emergence of a novel urogenital-tropic Neisseria meningitidis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021;34:34–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burns BL, Rhoads DD. Meningococcal urethritis: old and new. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60:

e0057522 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Bartley SN, Tzeng YL, Heel K, Lee CW, Mowlaboccus S, Seemann T, et al. Attachment and invasion of Neisseria meningitidis to host cells is related to surface hydrophobicity, bacterial cell size and capsule. PLoS One. 2013;8:

e55798 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Yee WX, Barnes G, Lavender H, Tang CM. Meningococcal factor H-binding protein: implications for disease susceptibility, virulence, and vaccines. Trends Microbiol. 2023;31:805–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tzeng YL, Sannigrahi S, Berman Z, Bourne E, Edwards JL, Bazan JA, et al. Acquisition of gonococcal AniA-NorB pathway by the Neisseria meningitidis urethritis clade confers denitrifying and microaerobic respiration advantages for urogenital adaptation. Infect Immun. 2023;91:

e0007923 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Brooks A, Lucidarme J, Campbell H, Campbell L, Fifer H, Gray S, et al. Detection of the United States Neisseria meningitidis urethritis clade in the United Kingdom, August and December 2019 - emergence of multiple antibiotic resistance calls for vigilance. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:

2000375 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Nguyen HT, Phan TV, Tran HP, Vu TTP, Pham NTU, Nguyen TTT, et al. Outbreak of sexually transmitted nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:2130–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taha MK. Simultaneous approach for nonculture PCR-based identification and serogroup prediction of Neisseria meningitidis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:855–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3140–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saito R, Nakajima J, Prah I, Morita M, Mahazu S, Ota Y, et al. Penicillin- and ciprofloxacin-resistant invasive Neisseria meningitidis isolates from Japan. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:

e0062722 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Wick RR, Judd LM, Holt KE. Performance of neural network basecalling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. 2019;20:129. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Comput Biol. 2017;13:

e1005595 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Tanizawa Y, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y. DFAST: a flexible prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline for faster genome publication. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1037–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, Holden MT, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Page AJ, Taylor B, Delaney AJ, Soares J, Seemann T, Keane JA, et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb Genom. 2016;2:

e000056 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W293–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takahashi H, Morita M, Kamiya H, Fukusumi M, Sunagawa M, Nakamura-Miwa H, et al. Genomic characterization of Japanese meningococcal strains isolated over a 17-year period between 2003 and 2020 in Japan. Vaccine. 2023;41:416–26. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ma KC, Unemo M, Jeverica S, Kirkcaldy RD, Takahashi H, Ohnishi M, et al. Genomic characterization of urethritis-associated Neisseria meningitidis shows that a wide range of N. meningitidis strains can cause urethritis. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:3374–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tettelin H, Saunders NJ, Heidelberg J, Jeffries AC, Nelson KE, Eisen JA, et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287:1809–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Retchless AC, Kretz CB, Chang HY, Bazan JA, Abrams AJ, Norris Turner A, et al. Expansion of a urethritis-associated Neisseria meningitidis clade in the United States with concurrent acquisition of N. gonorrhoeae alleles. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:176. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Biagini M, Spinsanti M, De Angelis G, Tomei S, Ferlenghi I, Scarselli M, et al. Expression of factor H binding protein in meningococcal strains can vary at least 15-fold and is genetically determined. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:2714–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sukhum KV, Jean S, Wallace M, Anderson N, Burnham CA, Dantas G. Genomic characterization of emerging bacterial uropathogen Neisseria meningitidis, which was misidentified as Neisseria gonorrhoeae by nucleic acid amplification testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:e01699–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bazan JA, Tzeng YL, Bischof KM, Satola SW, Stephens DS, Edwards JL, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profile for the US Neisseria meningitidis urethritis clade. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofac661.

- Willerton L, Lucidarme J, Walker A, Lekshmi A, Clark SA, Walsh L, et al. Antibiotic resistance among invasive Neisseria meningitidis isolates in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (2010/11 to 2018/19). PLoS One. 2021;16:

e0260677 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Kretz CB, Bergeron G, Aldrich M, Bloch D, Del Rosso PE, Halse TA, et al. Neonatal conjunctivitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis US urethritis clade, New York, USA, August 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:972–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Virji M, Makepeace K, Ferguson DJ, Achtman M, Sarkari J, Moxon ER. Expression of the Opc protein correlates with invasion of epithelial and endothelial cells by Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2785–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stephens DS, Spellman PA, Swartley JS. Effect of the (alpha 2—>8)-linked polysialic acid capsule on adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human mucosal cells. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:475–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McNeil G, Virji M, Moxon ER. Interactions of Neisseria meningitidis with human monocytes. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:153–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kolb-Mäurer A, Unkmeir A, Kämmerer U, Hübner C, Leimbach T, Stade A, et al. Interaction of Neisseria meningitidis with human dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6912–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hill DJ, Griffiths NJ, Borodina E, Virji M. Cellular and molecular biology of Neisseria meningitidis colonization and invasive disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2010;118:547–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sutherland TC, Quattroni P, Exley RM, Tang CM. Transcellular passage of Neisseria meningitidis across a polarized respiratory epithelium. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3832–47. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takahashi H, Kim KS, Watanabe H. Differential in vitro infectious abilities of two common Japan-specific sequence-type (ST) clones of disease-associated ST-2032 and carrier-associated ST-2046 Neisseria meningitidis strains in human endothelial and epithelial cell lines. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52:36–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stefanelli P, Colotti G, Neri A, Salucci ML, Miccoli R, Di Leandro L, et al. Molecular characterization of nitrite reductase gene (aniA) and gene product in Neisseria meningitidis isolates: is aniA essential for meningococcal survival? IUBMB Life. 2008;60:629–36. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barth KR, Isabella VM, Clark VL. Biochemical and genomic analysis of the denitrification pathway within the genus Neisseria. Microbiology (Reading). 2009;155:4093–103. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takahashi H, Kuroki T, Watanabe Y, Tanaka H, Inouye H, Yamai S, et al. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis isolates collected from 1974 to 2003 in Japan by multilocus sequence typing. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:657–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fukusumi M, Kamiya H, Takahashi H, Kanai M, Hachisu Y, Saitoh T, et al. National surveillance for meningococcal disease in Japan, 1999-2014. Vaccine. 2016;34:4068–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jolley KA, Maiden MCJ. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar