Volume 30, Number 4—April 2024

Research Letter

Ocular Dirofilariasis in Migrant from Sri Lanka, Australia

Abstract

We describe a case of imported ocular dirofilariasis in Australia, linked to the Hong Kong genotype of Dirofilaria sp., in a migrant from Sri Lanka. Surgical extraction and mitochondrial sequences analyses confirmed this filarioid nematode as the causative agent and a Dirofilaria sp. not previously reported in Australia.

Human dirofilariasis, caused by nematodes such as Dirofilaria repens or D. immitis, is a zoonotic disease transmitted through the bite of various mosquito species (1). The definitive hosts of Dirofilaria sp. nematodes are canine and feline populations. Clinical manifestations of human infections, including the development of nodules in multiple anatomic locations, result from the migration or dwelling of worms in subcutaneous tissues (1). Human dirofilariasis is typically species-specific depending on the geographic area; D. repens nematode infections are found in Europe and Asia and D. immitis nematode infections in the Americas (1). Recently, a new genotype, called Dirofilaria sp. hongkongensis in the literature and referred to in this article as Dirofilaria sp. Hong Kong genotype (2), is proposed as a causative agent of subcutaneous or subconjunctival dirofilariosis in humans with a likely reservoir in canines. Dirofilaria sp. Hong Kong genotype is considered a nomen nudum within the scientific community because a proper morphologic description is missing (3). In Australia, only 21 human cases of dirofilariasis have been reported (1). Four documented cases of orbital dirofilariasis have been linked to suspected Drofilaria infection (1).

Dirofilaria nematode infection is usually transmitted by mosquitoes (including those of the Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex genera) from carnivores. Mosquitoes play a crucial role in transmission by injecting the microfilaria into the accidental human host, which enables the transmitted larvae to develop further, but the nematodes do not typically reach full maturity in the human host, and they are usually sequestered in tissue. In rare instances, the adult stages of Dirofilaria nematodes are found in humans, usually in the lungs or in the cutaneous or subconjunctival areas (1).

In Australia, estimated prevalence of the D. immitis nematode in the canine population is 20% in some areas of the east coast, home to many species and genera of mosquitoes (e.g., Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex) (4,5,6). Of the 21 human dirofilariasis cases reported from mainland Australia in the past 40 years, most are linked to D. immitis nematode infection, and others are linked to D. repens nematode infection in returned travelers (1,4). We describe an imported case of human dirofilariasis of the Hong Kong genotype in Australia.

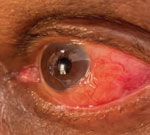

A 77-year-old man with a history of heart disease and diabetes was referred to the emergency department of the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, by an ophthalmologist because of concerns about a possible worm in the subconjunctiva. The patient had redness and pain in his left eye for 1 month but reported no visual impairment. He had immigrated from Sri Lanka to Melbourne 18 months earlier, and he had no history of recent travel, pet ownership, freshwater swimming, or gardening. Our examination of his left eye revealed normal visual acuity (6/6) and intraocular pressures (14 mm Hg). During the examination, we observed a mobile, whitish, curled, translucent, and elongated foreign body in the subconjunctiva positioned at approximately 4 o’clock, adjacent to the limbus, with an overlying mild conjunctival injection. Our posterior segment assessment of the eye (dilated pupil) was unremarkable (Figure 1). We surgically removed the foreign body, which was a 12-cm-long worm (Figure 2), after a limited peritomy (Appendix Figure). We then suspended the worm in physiologic saline and submitted it for macroscopic and genetic analysis. The patient was discharged the next day and returned for a follow-up examination 1 week later.

Our microscopic examination of the surgically removed worm confirmed that it was a female worm with a thick, nonridged cuticle and a complete alimentary tract and reproductive system. We found no larvae in the uterus. We genetically characterized the worm by using PCR-based sequencing of a portion of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase 1 (941 bp) gene and of the 12S nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (610 bp) (7). The sequences we obtained (GenBank accession nos. OR755977 and OR768484) were almost identical (940/941 bp for mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase 1; 610/611 bp for 12S) to those representing the Hong Kong genotype of the Dirofilaria nematode (GenBank accession no. KX265050).

We presume that the patient acquired the Dirofilaria nematode infection in Sri Lanka, where prevalence of dirofilariasis is high (30%–69%) in feline and canine populations and some cases are linked to the Hong Kong genotype (8). Of the 173 reported cases of human dirofilariasis caused by D. repens nematodes reported during 1965–2020, a total of 40 cases were in patients with subconjunctival infections (9). We are concerned that some of those infections might have been misidentified as D. repens because molecular methods were not used for genetic analysis and identification (8).

This study emphasizes the importance of using molecular tools for the accurate diagnosis of filariases and the need for heightened clinical suspicions of rare zoonotic infections. This emphasis is particularly important for patients who have a travel history from countries endemic for neglected tropical diseases.

Dr. Cope is a senior emergency registrar at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, Melbourne. He has an interest in ocular infections and diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carmel Crock for assistance and the patient for providing us permission to publish the findings.

This study was partially supported through a grant from the Australian Research Council.

References

- Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carretón E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis: the emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:507–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- To KK, Wong SS, Poon RW, Trendell-Smith NJ, Ngan AH, Lam JW, et al. A novel Dirofilaria species causing human and canine infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3534–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Perles L, Dantas-Torres F, Krücken J, Morchón R, Walochnik J, Otranto D. Zoonotic dirofilariases: one, no one, or more than one parasite. Trends Parasitol. 2024;S1471-4922(23)00312-4.

- Theodore SG, Sawkins HJ, Mathew M, Yadav S, Norton R. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis: an unexpected differential diagnosis for a solitary lung lesion. Med J Aust. 2023;219:455–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Constantinoiu C, Croton C, Paterson MBA, Knott L, Henning J, Mallyon J, et al. Prevalence of canine heartworm infection in Queensland, Australia: comparison of diagnostic methods and investigation of factors associated with reduction in antigen detection. Parasit Vectors. 2023;16:63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ong OTW, Skinner EB, Johnson BJ, Old JM. Mosquito-borne viruses and non-human vertebrates in Australia: a review. Viruses. 2021;13:265. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lefoulon E, Bain O, Bourret J, Junker K, Guerrero R, Cañizales I, et al. Shaking the tree: multi-locus sequence typing usurps current onchocercid (filarial nematode) phylogeny. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:

e0004233 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Atapattu U, Koehler AV, Huggins LG, Wiethoelter A, Traub RJ, Colella V. Dogs are reservoir hosts of the zoonotic Dirofilaria sp. ‘hongkongensis’ and potentially of Brugia sp. Sri Lanka genotype in Sri Lanka. One Health. 2023;17:

100625 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Iddawela D, Ehambaram K, Wickramasinghe S. Human ocular dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Sri Lanka. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;8:1022–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: March 12, 2024

Table of Contents – Volume 30, Number 4—April 2024

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Elliott Cope, The Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, 32 Gisborne St, East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Top