Volume 29, Number 5—May 2023

Research

Leishmania donovani Transmission Cycle Associated with Human Infection, Phlebotomus alexandri Sand Flies, and Hare Blood Meals, Israel1

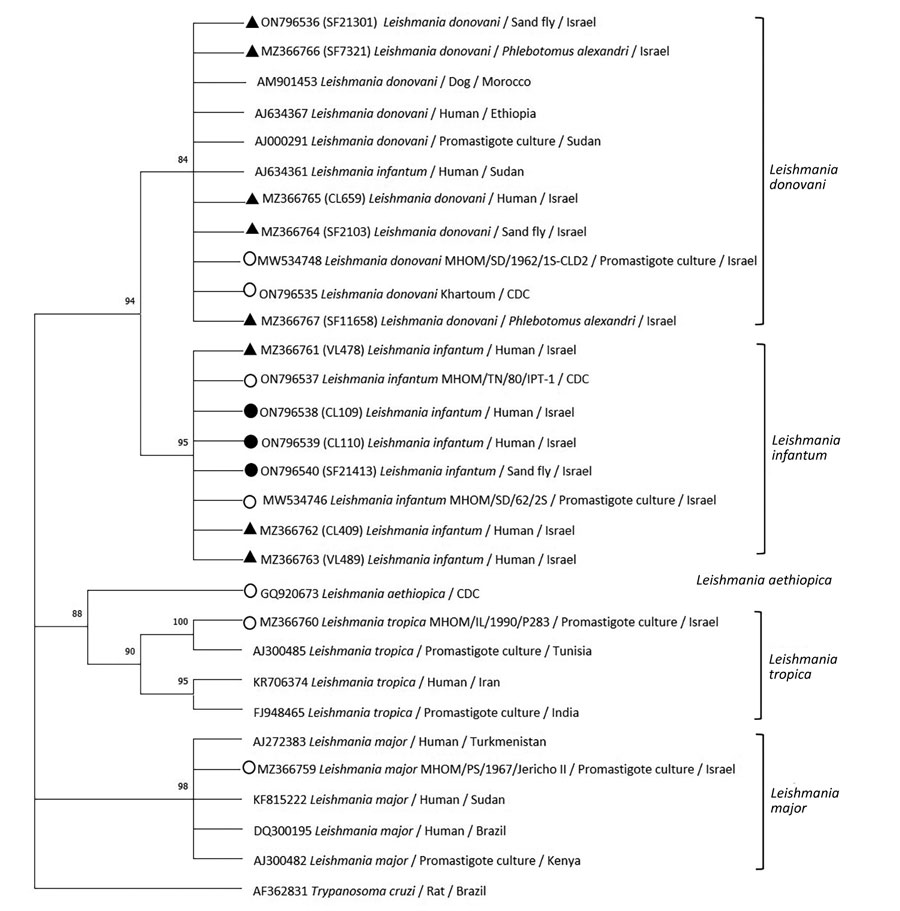

Figure 2

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of Leishmania internal transcribed spacer 1 rRNA fragments in study of Leishmania donovani transmission cycle associated with human infection, Phlebotomus alexandri sand flies, and hare blood meals, Israel. Leishmania-specific internal transcribed spacer 1 rRNA fragments (201 bp) were amplified by PCR from P. alexandri sand flies, pooled female Phlebotomus spp. flies, and patient samples and then sequenced. Tree was constructed by using the maximum-likelihood method and Tamura 3-parameter model, estimated by using the Aikaike information criterion (33). Dendogram includes sequences from L. donovani and L. infantum isolated from sand flies and clinical samples in this study compared with Leishmania spp. reference controls and GenBank sequences from Israel and other countries. Tree shows substantial separate clustering of L. infantum (boostrap 94%) and L. donovani (bootstrap 89%) sequences. Empty circles are Leishmania international reference strains, black triangles are the 10 sequences from our study deposited in GenBank, and black circles are additional L. infantum–positive sand flies samples from Israel. Available GenBank sequences for L. major, L. tropica, L. infantum, and L. donovani from Israel and other countries are also included. GenBank accession numbers, Leishmania spp., isolate source, and country are indicated. Only bootstrap values >70% are shown. Not to scale.

References

- Jaffe CL, Baneth G, Abdeen ZA, Schlein Y, Warburg A. Leishmaniasis in Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:328–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schlein Y, Warburg A, Schnur LF, Gunders AE. Leishmaniasis in the Jordan Valley II. Sandflies and transmission in the central endemic area. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982;76:582–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schlein Y, Warburg A, Schnur LF, Le Blancq SM, Gunders AE. Leishmaniasis in Israel: reservoir hosts, sandfly vectors and leishmanial strains in the Negev, Central Arava and along the Dead Sea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:480–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anis E, Leventhal A, Elkana Y, Wilamowski A, Pener H. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel in the era of changing environment. Public Health Rev. 2001;29:37–47.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jacobson RL, Eisenberger CL, Svobodova M, Baneth G, Sztern J, Carvalho J, et al. Outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in northern Israel. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1065–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schnur LF, Nasereddin A, Eisenberger CL, Jaffe CL, El Fari M, Azmi K, et al. Multifarious characterization of leishmania tropica from a Judean desert focus, exposing intraspecific diversity and incriminating phlebotomus sergenti as its vector. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:364–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Svobodova M, Votypka J, Peckova J, Dvorak V, Nasereddin A, Baneth G, et al. Distinct transmission cycles of Leishmania tropica in 2 adjacent foci, Northern Israel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1860–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jacobson RL. Leishmaniasis in an era of conflict in the Middle East. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:247–58. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ready PD. Biology of phlebotomine sand flies as vectors of disease agents. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:227–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gunders AE, Foner A, Montilio B. Identification of Leishmania species isolated from rodents in Israel. Nature. 1968;219:85–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gunders AE, Lidror R, Montilo B, Amitai P. Isolation of Leishmania sp. from Psammomys obesus in Judea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;62:465.

- Wasserberg G, Abramsky Z, Anders G, El-Fari M, Schoenian G, Schnur L, et al. The ecology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nizzana, Israel: infection patterns in the reservoir host, and epidemiological implications. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:133–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Faiman R, Abbasi I, Jaffe C, Motro Y, Nasereddin A, Schnur LF, et al. A newly emerged cutaneous leishmaniasis focus in northern Israel and two new reservoir hosts of Leishmania major. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:

e2058 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Talmi-Frank D, Jaffe CL, Nasereddin A, Warburg A, King R, Svobodova M, et al. Leishmania tropica in rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis) in a focus of human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:814–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ya’ari A, Jaffe CL, Garty BZ. Visceral leishmaniasis in Israel, 1960-2000. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6:205–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Singer SR, Abramson N, Shoob H, Zaken O, Zentner G, Stein-Zamir C. Ecoepidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis outbreak, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1424–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Azmi K, Krayter L, Nasereddin A, Ereqat S, Schnur LF, Al-Jawabreh A, et al. Increased prevalence of human cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel and the Palestinian Authority caused by the recent emergence of a population of genetically similar strains of Leishmania tropica. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;50:102–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gandacu D, Glazer Y, Anis E, Karakis I, Warshavsky B, Slater P, et al. Resurgence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel, 2001-2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1605–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Israel Ministry of Health. Annual report of central laboratories, 2019 (Hebrew) [cited 2021 Jan 5]. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/LAB_JER2019.pdf

- Nezer O, Bar-David S, Gueta T, Carmel Y. High-resolution species-distribution model based on systematic sampling and indirect observations. Biodivers Conserv. 2017;26:421–37. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Stern E, Gardus Y, Meir A, Krakover S, Tzoar H. Atlas of the Negev. Jerusalem (Israel): Keter Publishing House; 1986.

- Orshan L, Szekely D, Khalfa Z, Bitton S. Distribution and seasonality of Phlebotomus sand flies in cutaneous leishmaniasis foci, Judean Desert, Israel. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:319–28. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Orshan L, Elbaz S, Ben-Ari Y, Akad F, Afik O, Ben-Avi I, et al. Distribution and dispersal of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in a zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis focus, the northern Negev, Israel. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:

e0004819 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Abonnenc E. Les Phlébotomes de la région éthiopienne (Diptera, Psychodidae). In: Memoires ORSTOM series. Paris: Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique; 1972

- Lewis DJ. A taxonomic review of the genus Phlebotomus (Diptera: Psychodidae). Bull Br Mus Nat Hist. 1982;45:121–209.

- Lukes J, Mauricio IL, Schönian G, Dujardin JC, Soteriadou K, Dedet JP, et al. Evolutionary and geographical history of the Leishmania donovani complex with a revision of current taxonomy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9375–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Talmi-Frank D, Nasereddin A, Schnur LF, Schönian G, Töz SO, Jaffe CL, et al. Detection and identification of old world Leishmania by high resolution melt analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:

e581 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Sagi O, Berkowitz A, Codish S, Novack V, Rashti A, Akad F, et al. Sensitive molecular diagnostics for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:

ofx037 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Ben-Shimol S, Sagi O, Horev A, Avni YS, Ziv M, Riesenberg K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum in Southern Israel. Acta Parasitol. 2016;61:855–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- el Tai NO, Osman OF, el Fari M, Presber W, Schönian G. Genetic heterogeneity of ribosomal internal transcribed spacer in clinical samples of Leishmania donovani spotted on filter paper as revealed by single-strand conformation polymorphisms and sequencing. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:575–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haralambous C, Antoniou M, Pratlong F, Dedet JP, Soteriadou K. Development of a molecular assay specific for the Leishmania donovani complex that discriminates L. donovani/Leishmania infantum zymodemes: a useful tool for typing MON-1. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60:33–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valinsky L, Ettinger G, Bar-Gal GK, Orshan L. Molecular identification of bloodmeals from sand flies and mosquitoes collected in Israel. J Med Entomol. 2014;51:678–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ben-Ami R, Schnur LF, Golan Y, Jaffe CL, Mardi T, Zeltser D. Cutaneous involvement in a rare case of adult visceral leishmaniasis acquired in Israel. J Infect. 2002;44:181–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guan LR, Xu YX, Li BS, Dong J. The role of Phlebotomus alexandri Sinton, 1928 in the transmission of kala-azar. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64:107–12.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guan LR, Zhou ZB, Jin CF, Fu Q, Chai JJ. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) transmitting visceral leishmaniasis and their geographical distribution in China: a review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Molina R, Jiménez MI, Cruz I, Iriso A, Martín-Martín I, Sevillano O, et al. The hare (Lepus granatensis) as potential sylvatic reservoir of Leishmania infantum in Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2012;190:268–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sevá ADP, Martcheva M, Tuncer N, Fontana I, Carrillo E, Moreno J, et al. Efficacies of prevention and control measures applied during an outbreak in Southwest Madrid, Spain. PLoS One. 2017;12:

e0186372 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Tsokana CN, Sokos C, Giannakopoulos A, Mamuris Z, Birtsas P, Papaspyropoulos K, et al. First evidence of Leishmania infection in European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) in Greece: GIS analysis and phylogenetic position within the Leishmania spp. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:313–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rocchigiani G, Ebani VV, Nardoni S, Bertelloni F, Bascherini A, Leoni A, et al. Molecular survey on the occurrence of arthropod-borne pathogens in wild brown hares (Lepus europaeus) from Central Italy. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;59:142–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jambulingam P, Pradeep Kumar N, Nandakumar S, Paily KP, Srinivasan R. Domestic dogs as reservoir hosts for Leishmania donovani in the southernmost Western Ghats in India. Acta Trop. 2017;171:64–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hassan MM, Osman OF, El-Raba’a FM, Schallig HD, Elnaiem DE. Role of the domestic dog as a reservoir host of Leishmania donovani in eastern Sudan. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2:26. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dereure J, El-Safi SH, Bucheton B, Boni M, Kheir MM, Davoust B, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in eastern Sudan: parasite identification in humans and dogs; host-parasite relationships. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1103–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bsrat A, Berhe M, Gadissa E, Taddele H, Tekle Y, Hagos Y, et al. Serological investigation of visceral Leishmania infection in human and its associated risk factors in Welkait District, Western Tigray, Ethiopia. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2017;3:13–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bashaye S, Nombela N, Argaw D, Mulugeta A, Herrero M, Nieto J, et al. Risk factors for visceral leishmaniasis in a new epidemic site in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:34–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kalayou S, Tadelle H, Bsrat A, Abebe N, Haileselassie M, Schallig HDFH. Serological evidence of Leishmania donovani infection in apparently healthy dogs using direct agglutination test (DAT) and rk39 dipstick tests in Kafta Humera, north-west Ethiopia. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2011;58:255–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Magri A, Galuppi R, Fioravanti M, Caffara M. Survey on the presence of Leishmania sp. in peridomestic rodents from the Emilia-Romagna Region (North-Eastern Italy). Vet Res Commun. 2023;47:291–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Özbilgin A, Çavuş İ, Yıldırım A, Gündüz C. [Do the rodents have a role in transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Turkey?] [in Turkish]. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2018;52:259–72.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Frézard F, Aguiar MMG, Ferreira LAM, Ramos GS, Santos TT, Borges GSM, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of leishmaniasis: from the identification of critical physicochemical attributes to the design of effective topical and oral formulations. Pharmaceutics. 2022;15:99. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1Data from this study were presented at the Israeli Society for Parasitology, Protozoology and Tropical Diseases Annual Meeting; March 21, 2022; Kfar Hamaccabiah, Ramat Gan, Israel.